- Research Article

- Open access

- Published:

Dementia care pathways in prisons – a comprehensive scoping review

Health & Justice volume 12, Article number: 2 (2024)

Abstract

Background

The number of older people in prison is growing. As a result, there will also be more prisoners suffering from dementia. The support and management of this population is likely to present multiple challenges to the prison system.

Objectives

To examine the published literature on the care and supervision of people living in prison with dementia and on transitioning into the community; to identify good practice and recommendations that might inform the development of prison dementia care pathways.

Methods

A scoping review methodology was adopted with reporting guided by the PRISMA extension for scoping reviews checklist and explanation.

Results

Sixty-seven papers were included. Most of these were from high income countries, with the majority from the United Kingdom (n = 34), followed by the United States (n = 15), and Australia (n = 12). One further paper was from India.

Discussion

The literature indicated that there were difficulties across the prison system for people with dementia along the pathway from reception to release and resettlement. These touched upon all aspects of prison life and its environment, including health and social care. A lack of resources and national and regional policies were identified as important barriers, although a number of solutions were also identified in the literature, including the development of locally tailored policies and increased collaboration with the voluntary sector.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is the most comprehensive and inclusive review of the literature on dementia care pathways in prison to date. It has identified a number of important areas of concern and opportunities for future research across the prison system, and its operations. This will hopefully lead to the identification or adaptation of interventions to be implemented and evaluated, and facilitate the development of dementia care pathways in prisons.

Background

The number of older people (defined here as those over 50Footnote 1) being held in prison in England and Wales has almost tripled over the last 20 years, and they now represent 17.1% of that population (Ministry of Justice, 2022a). The growing number of older people has brought with it an increasing number of health and social care problems, reportedly affecting around 85% of older people in prison, with associated costs (Di Lorito, et al., 2018; Hayes et al., 2012, 2013; Senior, et al., 2013). It has been estimated that 8.1% of those over the age of 50 in prison have mild cognitive impairment or dementia, which is much higher than estimates for this age group in the general population (Dunne et al., 2021; Forsyth et al., 2020). This pattern of poor health also increased the vulnerability of older people in prison during the pandemic (Kay, 2020).

Prison policy and legislation mandates that health and social care be ‘equivalent’ to that provided in the community (Care Act, 2014; Department of Health, 1999). Despite this, provisions are reportedly inconsistent, and the government has been described as ‘failing’ in its duty of care (Health and Social Care Committee, 2018; HM Inspectorate of Prisons & Care Quality Commission, 2018). This is likely exacerbated by the suspension and limiting of healthcare services during the pandemic, noted to have had a ‘profound’ impact on people’s health and wellbeing (HM Inspectorate of Prisons, 2021). This may be particularly so for people living in prison with dementia (PLiPWD), whereby the difficulties of delivering health and social care are compounded by inappropriate buildings, environments, and prison regimes (rules and regulations). In addition, PLiPWDs may experience an increase in social isolation, including separation from friends and family, all of which may make their time in prison more challenging (Moll, 2013; Peacock et al., 2019).

There is no current national strategy for older people in prison in England and Wales, including PLiPWD, although the British government recently agreed that there is a need for one (Justice Committee, 2020). A ‘Model for Operational Delivery’ for older people has been published by Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service (2018) in England and Wales, though this is guidance only and the “properly resourced and coordinated strategy” previously called for has not been produced (Prisons & Probation Ombudsman, 2017, p7; Brooke and Rybacka, 2020; HM Inspectorate of Prisons, 2019; Justice Committee, 2020). One way of attempting to standardise and improve the quality of treatment and care in the community has been through the use of care pathways (Centre for Policy on Ageing, 2014; Schrijvers et al., 2012). Care pathways have been defined as “a complex intervention for the mutual decision-making and organisation of care processes for a well-defined group of patients during a well-defined period”, involving an articulation of goals and key aspects of evidence-based care, coordination and sequencing of activities and outcomes evaluation (Vanhaecht, et al., 2007, p137).

The development of care pathways within the prison system lags behind that of the community, but the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has produced a pathway for prisoner health for England and Wales (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2019), and there is a care pathway for older prisoners in Wales (Welsh Government & Ministry of Justice, 2011). There has also recently been an overall care pathway developed for people in prison with mild cognitive impairment and dementia, although this has not been implemented as yet, and it does not include any details regarding release and resettlement (Forsyth et al, 2020). It has been recommended that care pathways should be developed locally, as they are context-sensitive, should be viewed as processual and flexible, and the needs of the person, their experiences and characteristics need to be taken into account – such as age, gender and race (Centre for Policy on Ageing, 2014; Pinder, et al., 2005).

Here we review the current literature on people living in prison with dementia. There have been two recent systematic literature reviews conducted on PLiPWD, both of which only included primary research studies that were small in number (Brooke and Rybacka, 2020 (n = 10); Peacock et al., 2019 (n = 8)), and focused on prevalence, identification (screening and diagnosis), and the need for tailored programming and staff training. Peacock et al., (2019) identified dementia as a concern and suggested recommendations for improved screening and care practices. Brooke et al. (2020) noted that, whilst the prevalence of dementia in prison populations was largely unknown, there was a need for national policies and local strategies that support a multi-disciplinary approach to early detection, screening and diagnosis. Neither paper, however, reported on the much more extensive and rich grey literature in this area (Brooke and Rybacka, 2020), to help comprehensively identify the systemic and operational problems, barriers and potential solutions that would be useful to consider in developing local dementia care pathways. Therefore, the aim of this paper is to conduct a comprehensive systematic scoping review of the available published literature on the support and management of PLiPWD in prison and upon transitioning into the community, and to identify practice and recommendations that would be useful to consider in the development of a local prison dementia care pathway.

Methods

A scoping review methodology using Arksey and O’Malley’s (2005) five-stage framework was adopted for this review. Reporting was guided by the PRISMA extension for scoping reviews checklist and explanation (Tricco et al., 2018). The completed checklist for this review is available in Additional file 1: Appendix 1.

Identification of relevant reports

The search strategy was formulated by the research team, and included an electronic database search and subsequent hand search. The electronic search involved searching twelve electronic databases: Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstract, Criminal Justice Abstracts, Embase, Medline (OVID), National Criminal Justice Reference Service, Open Grey, Psycinfo, Pubmed, Scopus, Social Services Abstracts, Sociological Abstracts, and Web of Science. The search combined condition-related terms (dementia OR Alzheimer*) AND context-related ones (prison OR jail OR gaol OR penitentia* OR penal OR correctional* OR incarcerat*), with no date or language restrictions, and covered the full range of publications up until April 2022. Additional file 2: Appendix 2 has an example of the search strategy used.

Electronic searches were supplemented by comprehensive hand searching and reference mining. Searches were also undertaken using: search engines; websites related to prisons and/or dementia (for example, Prison Reform Trust); a database from a previous related literature review (Lee et al, 2019); recommendations from academic networking sites; contacting prominent authors in the field directly; government-related websites (for example Public Health England, now called Health Security Agency); recent inspection reports for all prisons in England and Wales from Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Prisons and the Independent Monitoring Board.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Papers were considered suitable for inclusion in this review if they met the following criteria:

-

(i)

Setting: Papers should primarily be set in, or pertain to, prisons. Documents solely referring to community services, hospitals or medical facilities that are not part of the prison system were excluded.

-

(ii)

People: Papers involving PLiPWD. Research focused only on older people in prison more generally was excluded, as was research which described the disorienting effects of imprisonment more generally, but which was not related to dementia.

-

(iii)

Intervention: Some consideration of the treatment, care, support or management of PLiPWD; this can be health or social-care associated, as well as related to the prison overall, and to any individuals, groups or agencies who visit or work with individuals during their time in prison (including family, friends, charities, probation services). Papers which mostly describe prevalence studies, sentencing practices or profiles were excluded.

-

(iv)

Study design: All designs were considered for inclusion. Editorials, book reviews, online blogs, press releases, announcements, summaries, newspaper and magazine articles, abstracts and letters were excluded.

The titles, abstracts and full-text of the papers identified by the searches were screened for inclusion in the review. The screening was undertaken by two independent researchers (ST and NS) for inter-rater reliability purposes (Rutter et al., 2010). Any differences of opinion on inclusion were resolved between the researchers (ST, NS and SM), and with the Principle Investigator (TVB).

Charting the data

An extraction template was developed for the review, guided by the PICO formula (Richardson et al., 1995) and informed by pathway stages and key areas highlighted in the older prisoner pathways toolkit for England and Wales (Department of Health, 2007), and the older prisoner pathway formulated for Wales (Welsh Government & Ministry of Justice, 2011). Using this extraction template, all of the data was extracted from the included papers by one member of the research team (ST), with a second researcher extracting data from a third of the papers as a check for consistency (SM). Any unresolved issues were related to the Principle Investigator (TVB) for resolution.

Collating, summarising and reporting results

The review was deliberately inclusive of a wide variety of types of papers, which meant that taking a meta-analytic approach to the data was not feasible. Therefore, a narrative approach to summarising and synthesising the findings and recommendations of the included papers was adopted (Popay et al, 2006).

Results

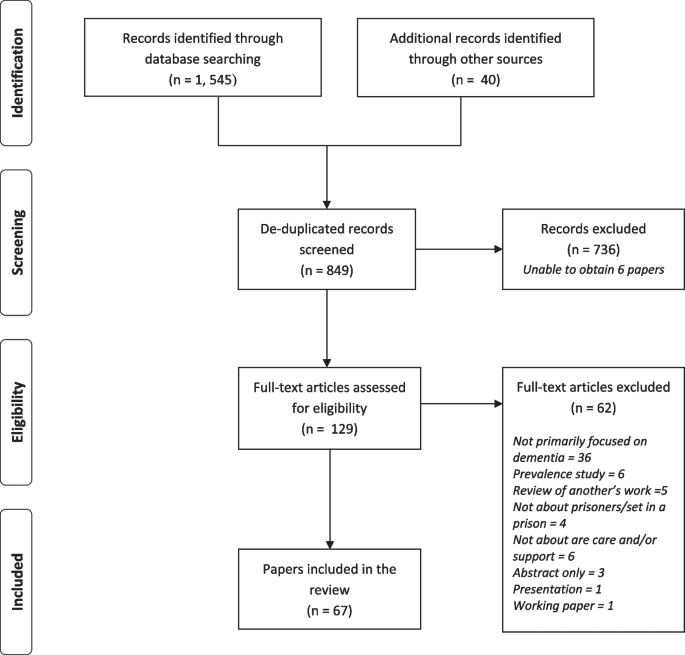

Sixty-seven papers were included in this scoping review. The screening process phases conducted by the research team are shown in Fig. 1.

A brief overview of the key features of each of the papers is presented in Table 1. All but one of the included papers were from high income countries, with the majority from the United Kingdom (n = 34), and then the United States (n = 15), Australia (n = 12), Canada (n = 4), Italy (n = 1) and India (n = 1). The papers were split into types, with twenty-two guidance and inspection documents, and twenty-seven discussion and intervention description papers. Of the eighteen research and review articles with a defined methodology included there were four literature reviews (one was systematic), nine qualitative studies, four mixed-methods studies (one which followed participants up), and one survey-based study.

Areas to consider in the support and management of PLiPWD during their time in prison and upon their release

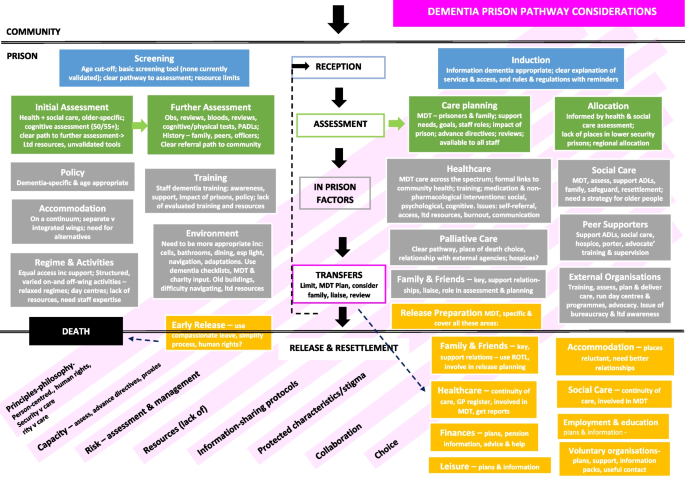

The pathway through the prison is shown in Fig. 2, and typically involves: (i) reception into prison; (ii) assessments, and allocation of the person within prison; (iii) time held in prison; (iv) transfers between prisons, and between prisons and other services such as time spent in hospital; and (v) release and preparations for resettlement in the community. There were also a number of (vi) cross-cutting themes which could potentially impact people with dementia living in prison at each stage across the prison pathway.

(i) Reception

Upon entry into prison, prisoners are subject to an initial reception screening to identify and support immediate health and social care problems, and those in need of further assessment. An induction to prison rules and regulations also typically occurs at this step.

Screening

All papers reported that reception screening with appropriate screening tools was important in identifying cognitive difficulties and in establishing a baseline, but implementation seemed to vary (Peacock et al., 2019). One study in England and Wales found only 30% of prisons contacted routinely did this (Forsyth et al., 2020). Supporting policy and a service/person to refer to directly for further assessment were also highlighted as useful (Brooke & Jackson, 2019; Brooke et al., 2018; Gaston & Axford, 2018; Inspector of Custodial Services, 2015; Patterson et al., 2016). Proposed cut-offs for this screening were either 50 years of age (n = 7), under 55 years (n = 1), or 55 years of age (n = 7). One paper reported that only a third of prisoners who were offered this screening accepted it, although the reasons for this were not stated (Patel & Bonner, 2016). Another paper suggested that a screening programme could have unintended adverse consequences, that could damage already fragile relationships between staff and people living in prison (Moore & Burtonwood, 2019). Whilst many screening tools were mentioned, there are currently no tools validated for use in prisons, and many of those used in the community may be inappropriate (Baldwin & Leete, 2012; Brooke et al., 2018; du Toit et al., 2019; Feczko, 2014; Forsyth et al., 2020; Moore & Burtonwood, 2019; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2017; Turner, 2018; Williams et al., 2012). One validation study found that the Six-item Cognitive Impairment Test (6CIT) was not suitably sensitive for use (Forsyth et al., 2020). Other difficulties included the limited amount of time and resources available to screen at reception (Christodoulou, 2012; Patterson et al., 2016; Peacock et al., 2019), and that staff lacked ‘familiarity’ with screening tools (Peacock et al., 2019).

Induction

Only two papers mentioned the induction process (Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018; Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011) as important. A need for clearly explained information in a dementia-appropriate format (written and verbal) particularly regarding healthcare, and a recommendation that PLiPWD should be regularly reminded of rules and regulations, were suggested.

(ii) Assessment

Following the screening process, the current recommendation is that an initial healthcare assessment takes place in the first seven days after entering prison. During this initial assessment period, although not necessarily within this timeframe, care plans and allocation decisions may also be made regarding where the prisoner is placed within the prison.

Assessment

An initial older-person-specific health and/or social care assessment or standard process for assessment has been recommended by ten papers, six of which were from government or related bodies. It was also suggested by some papers, that a cognitive assessment should take place at either 50 years (n = 6) or 55 years (n = 2), which should be repeated every three months (n = 3), six months (n = 5) or annually (n = 12), with the latter including recommendations from NICE guidelines (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2017). One study set in England and Wales found that most prisons (60%) that screened older people, did so between 7–12 months (Forsyth et al., 2020). Brief and affordable tools were considered more useful (Garavito, 2020; Turner, 2018), although the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MOCA) was recommended in the care pathway developed by Forsyth et al. (2020).

Typically, assessments were conducted by healthcare staff, GPs or a psychologist (n = 6), a specialist in-house assessment unit (n = 2), or a specific dementia admissions assessment unit (n = 4). For further assessment, some prisons had internal teams to refer to (n = 5). Forsyth et al. (2020) recommend referral to external Memory Assessment Services for assessment. A case finding tool was being piloted in one prison (Sindano & Swapp, 2019). Assessments included can be found in Table 2.

Assessments also explored risk and safeguarding (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2017; Patterson et al., 2016; Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011), environmental impact (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2017), capacity (Prison & Probation Ombudsman, 2016), work, education, and drug and alcohol use (Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011) and a person’s strengths (Hamada, 2015; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2017). Prison staff contributed to some assessments of activities of daily living (ADLs) or prison-modified ADLs (Brooke et al., 2018; Brown, 2016; Dillon et al., 2019; Department of Health, 2007; Feczko, 2014; Forsyth et al., 2020; Gaston, 2018; Gaston & Axford, 2018; Patterson et al., 2016; Turner, 2018; Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011; Williams et al., 2012). Challenges to Assessment can be found in Table 3.

Care plans

Twelve papers described or recommended care planning post-assessment, in collaboration with PLiPWD and primary care, or a multi-disciplinary team (MDT) of health, social care and prison staff with external specialists healthcare proxies charities or family (Brown, 2016; Dillon et al., 2019; du Toit & Ng, 2022; Hamada, 2015; Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Prisons, 2014; Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018; Moll, 2013; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2017; Patterson et al., 2016; Prisons and Probation Ombudsman, 2016; Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011). However, it was suggested that prison staff be removed from the decision-making process as the dementia progresses, and be part of the ‘duty of care’ of healthcare staff and services (du Toit & Ng, 2022). It was recommended too that care plans be disseminated to prison wing staff (Forsyth et al., 2020) and peer supporters (Goulding, 2013), and that consent be sought for this (Goulding, 2013; Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Prisons, 2014) An ombudsman report in England and Wales noted that care plans for PLiPWD who had died in prison were inadequate (Peacock et al., 2018), and of the varying degrees of care planning found by Forsyth et al (2020), it was described typically as “rudimentary” (p26). Care plans are described further in Table 4.

Allocation

Many papers reported that prisons did or should make decisions about where people should be accommodated within the prison after health assessments (Brown, 2016; Feczko, 2014; Forsyth et al., 2020; Hodel & Sanchez, 2013; Inspector of Custodial Services, 2015; Mistry & Muhammad, 2015; Turner, 2018; Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011; Williams et al., 2012), taking age and health into account. However, despite recommendations that PLiPWD should be placed on the ground floor on low bunks for instance (Baldwin & Leete, 2012; Department of Health, 2007; Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011), there were reports that this was not happening (Inspector of Custodial Services, 2015). There were also recommendations for allocations to be made across a region to ensure people are appropriately placed in the prison system (Baldwin & Leete, 2012; Booth, 2016; Gaston & Axford, 2018; Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011). Concerns were expressed about the lack of lower category places for PLiPWD (Department of Health, 2007), and the lack of guidance regarding placement of people with high support needs (Sindano & Swapp, 2019) in England and Wales.

(iii) Within-prison issues

Policy

A number of papers reported on a need for policies or frameworks to support staff to identify, assess and support people who may be living with dementia (Brooke et al., 2018; Brooke & Jackson, 2019; Department of Health, 2007; Feczko, 2014; Gaston, 2018; Gaston & Axford, 2018; Patterson et al., 2016; Turner, 2018; Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011), without which staff have faced difficulties in providing quality care and support (Feczko, 2014; Prisons and Probation Ombudsman, 2016). Whilst there were some examples of guidance for dementia (Hamada, 2015; Patterson et al., 2016; Treacy et al., 2019; Turner, 2018), it was suggested that all policies should be reviewed and amended to ensure that they are appropriate for older people and people living with dementia (Department of Health, 2007; Lee et al., 2019; Treacy et al., 2019). Specific policy areas are described in Table 5.

Training

Issues around staff training on dementia were discussed in the majority of papers (n = 54) Many of these reported that prison staff either lacked training on dementia, or that training was limited (n = 16), with one study in England and Wales reporting that only a quarter of prison staff had received such training (Forsyth et al., 2020). Perhaps consequently, a number of papers identified that prison staff required some dementia training (n = 19). Staff working on a specialist dementia unit reportedly had a comprehensive 40-h training (Brown, 2014, 2016; Gaston & Axford, 2018; Hodel & Sanchez, 2013; Moll, 2013), and it was suggested that more comprehensive training be facilitated for officers, particularly those working with PLiPWD (n = 18) and offender managers (n = 2). A need for all staff working with PLiPWD to be supervised was also suggested (Gaston & Axford, 2018; Maschi et al., 2012). Despite a lack of consensus on content and duration (du Toit et al, 2019), typically, the staff training undertaken and recommended was in four areas (Table 6). It was also recommended that training for healthcare could be more comprehensive and focused on screening, identification, assessment, diagnoses, supervision and intervention training (Baldwin & Leete, 2012; Brooke & Jackson, 2019; Brown, 2014; Gaston & Axford, 2018; Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Prisons, 2014; Moll, 2013; Moore & Burtonwood, 2019; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2017; Peacock et al, 2019; Treacy et al, 2019; Turner, 2018; Williams, 2014). It is of note that only 21% of healthcare staff in one study in England and Wales reported attending training to identify dementia (Forsyth et al., 2020), similar to the figures regarding prison staff in the same study.

Much of the training described in the included papers had been formulated and delivered by dementia- or older people-specific voluntary organisations (Alzheimer’s Society, 2018; Brooke et al. 2018; Brown, 2016; Gaston & Axford, 2018; HMP Hull, 2015; Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018; Hodel & Sanchez, 2013; Moll, 2013; Peacock et al., 2018; Prisons and Probation Ombudsman, 2016; Sindano & Swapp, 2019; Tilsed, 2019; Treacy et al., 2019). Although it has also been recommended to involve health and social care (Goulding, 2013; Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018; Ministry of Justice, 2013; Treacy et al., 2019; Turner, 2018), and officers and peer supporters (Brooke & Jackson, 2019; Masters et al., 2016; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2017; Treacy et al., 2019) in developing the training. In one study, prison staff were also trained to deliver dementia information sessions to their peers (Treacy et al., 2019). A suggestion of video-training packages was also made (du Toit et al., 2019). Dementia training typically lacked robust evaluation (Brooke et al., 2018), although those available generally reported benefits in their understanding of dementia, relationships, and diagnoses (Goulding, 2013; HMP Littlehey, 2016; Masters et al., 2016; Sindano & Swapp, 2019; Treacy et al., 2019). It was also reported that some prison staff were resistant to working with PLiPWD (Moll, 2013), and that resource limitations resulted in training cuts (HMP Hull, 2015; Treacy et al., 2019).

Healthcare

Offering healthcare across the spectrum for PLiPWDs, from acute to chronic care, with a focus on preventative and long-term care as well as palliative care was recommended by some papers (Brown, 2014; du Toit & Ng, 2022; Gaston, 2018; Maschi et al., 2012; Mistry & Muhammad, 2015; Peacock et al, 2018; Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011; Williams et al., 2012). The development of care pathways to guide this were also recommended or formulated (du Toit et al., 2019; Forsyth et al., 2020; Peacock et al., 2019), although the majority (69%) of prisons in one study in England and Wales did not have one (Forsyth et al., 2020). Clear and formal links with local hospitals, memory clinics, forensic and community teams for planning, training, advice, support and in-reach were also present or recommended by sixteen research and guidance papers. The amount of healthcare cover in prisons in England and Wales reportedly varied with the function of the prison with largely only local prisons having 24-h healthcare staff (Treacy et al., 2019), and most other forms of prison having office-type hours’ healthcare cover – including sex offender prisons where the majority of older prisoners are held (Brown, 2016; Correctional Investigator Canada, 2019; Goulding, 2013; Inspector of Custodial Services, 2015; Treacy et al., 2019). While specialist services or units for PLiPWD exist in a number of jurisdictions (Baldwin & Leete, 2012; Brown, 2016; Cipriani et al., 2017; Gaston & Axford, 2018; Goulding, 2013; Hodel & Sanchez, 2013; Inspector of Custodial Services, 2015; Maschi et al., 2012; Mistry & Muhammad, 2015; Treacy et al, 2019), more are reportedly needed (Brooke et al., 2018; du Toit et al., 2019; Forsyth et al., 2020; Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011).

Most healthcare teams were reportedly MDT, or this was recommended, alongside joint health and social care working (n = 16). A number of healthcare staff acted as the lead for older people in prisons (Department of Health, 2007; Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Prisons, 2014; Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Prisons, 2016; Moll, 2013; Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011), with a recommendation that a dementia-trained nurse should lead any dementia care pathways (Forsyth et al., 2020) and indeed it was suggested that healthcare staff in general have training and experience in working with older people (Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Prisons, 2014; Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Prisons, 2017b; Moll, 2013; Patterson et al., 2016; Public Health England, 2017b; Treacy et al., 2019; Turner, 2018; Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011). Whilst one of the recommended roles for healthcare was the prescription and monitoring of medication (Feczko, 2014; Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Prisons, 2017b; Moll, 2013), much of the focus was on early identification and diagnosis, and keeping a dementia register (Department of Health, 2007; Moll, 2013; Patterson et al., 2016; Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011), and the use of non-pharmacological approaches. These broadly included: psychological interventions (Goulding, 2013; Hamada, 2015; Moll, 2013; Wilson & Barboza, 2010); assistance with ADLs and social care (Feczko, 2014; Hamada, 2015; Hodel & Sanchez, 2013; Maschi, et al., 2012; Murray, 2004; Prisons and Probation Ombudsman, 2016); development and delivery of specialist dementia prison programmes (Brown, 2014, 2016; Hodel & Sanchez, 2013; Mistry & Muhammad, 2015; Moll, 2013; Peacock et al., 2018; Wilson & Barboza, 2010); reablement and rehabilitation (Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011); relaxation (Wilson & Barboza, 2010); safeguarding (Hodel & Sanchez, 2013); and cognitive stimulation groups (Moll, 2013; Williams, 2014). Other possible roles included: training or supporting staff and peer supporters, as reported in fourteen papers, as well as advocacy (Feczko, 2014; Peacock et al., 2018; Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011), allocation, assessment for offending behaviour groups, risk assessments and disciplinary hearings (Booth, 2016; Department of Health, 2007; Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018; Murray, 2004; Prisons and Probation Ombudsman, 2016). Challenges to Healthcare are noted in Table 7.

Palliative care

A care pathway for dying people that meets community standards was recommended (Department of Health, 2007; Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018; Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011), as was ensuring that people could choose a preferred place to die (Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018). Some prisoners were moved to community hospices or hospitals (Brooke & Jackson, 2019; Inspector of Custodial Services, 2015), or it was felt that they should be (Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018). Although it was noted that some prisons lack relationships with community hospices or palliative care services and need to foster them (Brooke & Jackson, 2019; Brown, 2016; Correctional Investigator Canada, 2019; Department of Health, 2007; Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018).

A number of prisons also reportedly had hospices, particularly in the United States (Brooke et al., 2018; Brown, 2016; Feczko, 2014; Goulding, 2013; Williams et al., 2012), although these have not been comprehensively evaluated (Williams et al., 2012). It was recommended that these be staffed by MDTs (Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018), including chaplains and nutritionists (Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018; Goulding, 2013), and many included prisoner peer supporters (Brooke et al., 2018; Goulding, 2013). The use of independent contractors was also suggested as staff-prisoner relationships were considered problematic in some prisons (Williams et al., 2012). Regarding family, many hospices were described as allowing more visits (Brooke & Jackson, 2019; Goulding, 2013; Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018), including one prison with family accommodation (Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018). Whilst re-engaging with family was reportedly encouraged (Brown, 2016), a lack of support was noted (Correctional Investigator Canada, 2019). Suggested improvements include a family liaison officer, providing a list of counselling options, and hosting memorial services (Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018).

Social care

A social care strategy for older prisoners and a social care lead for all prisons in England and Wales has been recommended (Department of Health, 2007; Prisons and Probation Ombudsman, 2016). It was reported that MDTs working with PLiPWD should and increasingly do include social workers including specialist units and hospices (Baldwin & Leete, 2012; Brooke et al., 2018; Brown, 2016; Cipriani et al., 2017; Goulding, 2013; HMP Littlehey, 2016; Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018; Maschi et al., 2012; Prisons and Probation Ombudsman, 2016; Sindano & Swapp, 2019; Treacy et al., 2019; Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011). Social care roles can be found in Table 8.

The work may be direct or may be through co-ordinating external agencies or peer supporters (Brooke & Jackson, 2019; Department of Health, 2007; Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018; Prisons and Probation Ombudsman, 2016; Tilsed, 2019; Treacy et al., 2019; Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011). Clarity in these roles was considered paramount, particularly as uncertainty reportedly continues to exist over who is responsible for meeting prisoners’ social care needs in some prisons in England and Wales despite the passing of the Care Act, 2014 (Dementia Action Alliance, 2017; Tilsed, 2019; Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011). There was also some ambiguity around the threshold PLiPWD were expected to meet in order to access social care (Forsyth et al., 2020). In some instances, personal care was delivered informally by untrained and unsupported prison staff and peer supporters in lieu of suitably trained social care workers (Treacy et al., 2019), with issues raised about the unavailability of social care through the night (Forsyth et al., 2020). Where social care staff were involved in coordinating personal care for prisoners, it was reported as positive for prisoners and prison staff (Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Prisons, 2016; Treacy et al., 2019), particularly, in one prison, where social care staff were prison-based (Forsyth et al., 2020).

Peer supporters

Prisoner peer supporters were operating in a number of prisons, as reported in 22 papers, and their employment was recommended by a further fourteen. Typically, these were people who had ‘good’ disciplinary and mental health records, and certainly in the US, were longer-serving prisoners. A number of papers indicated the need for peer supporters to receive training in dementia, including awareness and support (Brooke et al., 2018; Brooke & Jackson, 2019; Brown, 2016; Correctional Investigator Canada, 2019; Department of Health, 2007; Dillon et al., 2019; du Toit & Ng, 2022; Gaston, 2018; Gaston & Axford, 2018; Goulding, 2013; HMP Hull, 2015; HMP Littlehey, 2016; Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018; Inspector of Custodial Services, 2015; Maschi et al., 2012; Mistry & Muhammad, 2015; Sindano & Swapp, 2019; Tilsed, 2019; Treacy et al., 2019). Comprehensive 36–40 h training on dementia was delivered for those working on specialist units, including one leading to a qualification (Brooke & Jackson, 2019; Brown, 2016; Gaston & Axford, 2018; Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018; Moll, 2013). Much of the training was developed and delivered by charities, particularly dementia-related ones, as reported in eleven papers. Ongoing support and supervision was offered or recommended by some prisons, provided largely by health or social care staff or charities (Brooke & Jackson, 2019; Brown, 2016; Correctional Investigator Canada, 2019; Department of Health, 2007; Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018; Gaston & Axford, 2018; Maschi et al., 2012; Prisons and Probation Ombudsman, 2016; Sindano & Swapp, 2019; Treacy et al., 2019), with informal peer-to-peer support also described (Brown, 2016; Gaston & Axford, 2018; Treacy et al., 2019). The support and supervision received was found to be valuable (Brooke & Jackson, 2019; Brown, 2016; Treacy et al., 2019). Peer-supporter roles are listed in Table 9.

A number of benefits to: (a) the peer supporters, (b) the prisoners they supported and, (c) the prison, were described, although formal evaluations were lacking (Brown, 2016; Christodoulou, 2012; Department of Health, 2007; du Toit et al., 2019; Gaston, 2018; Gaston & Axford, 2018; Goulding, 2013; Treacy et al., 2019; Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011). This included: payment, development of skills which could be used on release, positive impact on progression through the system, and on self-confidence and compassion, and the creation of a more humane environment. However, frustration and distress amongst peer supporters largely when untrained and unsupported was also reported (Brooke & Jackson, 2019; Brown, 2016; Correctional Investigator Canada, 2019; Inspector of Custodial Services, 2015; Prisons and Probation Ombudsman, 2016; Treacy et al., 2019), and concerns raised in relation to an over-reliance on peers to do work that it is the statutory duty of health and social care to provide (Prisons and Probation Ombudsman, 2016; Treacy et al., 2019). This was a particular problem in light of personal care being prohibited for peer supporters in England and Wales (Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018; Moll, 2013). It is also of note that the role of peer supporter may also attract the opprobrium of other prisoners, with reports that they have been seen as ‘snitches’ or ‘dogs’ in some areas (Brown, 2016; Goulding, 2013). In addition, in some prisons, the peer supporter role was not advocated due to: fear of litigation; fear of replacing staff with peers; belief that people should be acquiring more transferable skills, since many would be unable to undertake care work in the community due to their offence history (Brown, 2016; Goulding, 2013).

Accommodation

There were mixed views regarding accommodation for PLiPWD. A continuum of prison accommodation was suggested from independent to 24-h care (including assisted living) (Forsyth et al., 2020; Gaston & Axford, 2018; Williams et al., 2012). A number of papers (n = 18) recommended that there should be some form of alternative, more appropriate accommodation developed, potentially regional, including secure facilities possibly with a palliative orientation (Hodel & Sanchez, 2013; Mistry & Muhammad, 2015; Sfera et al., 2014). However, there were concerns about the availability, costs and staffing of specialist units, and distances that family would have to travel to visit despite potential benefits (du Toit et al., 2019; Moore & Burtonwood, 2019). It was also suggested that PLiPWD should be released to live in the community instead (Correctional Investigator Canada, 2019).

Within prisons, there was a debate evident within the papers about whether PLiPWD should be accommodated in separate units or integrated within the general prison population, which had generated little clear evidence and mixed views (Brooke & Jackson, 2019; Dillon et al., 2019; Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018; Treacy et al., 2019). Authors have suggested that specialist or separate wings focused on older people or those with dementia were safer, met peoples’ needs better, and offered better care, support and programmes than integrated units (Brown, 2014; Dillon et al., 2019; du Toit & Ng, 2022; du Toit et al., 2019; Goulding, 2013; Maschi et al., 2012; Murray, 2004; Treacy et al., 2019; Williams et al., 2012), as long as they were ‘opt-in’ for prisoners and staff (Correctional Investigator Canada, 2019; Moll, 2013; Treacy et al., 2019; Williams et al., 2012), and opportunities to get off the wing to socialise with others are provided (Treacy et al., 2019). The types of ‘specialist’ accommodation that PLiPWD were living in are reported in Table 10. It is of note that papers reported a highly limited number of beds available in specialist units (Inspector of Custodial Services, 2015; Patterson et al., 2016; Turner, 2018), and that a number of older prisoner-specific prisons were being closed due to costs (Turner, 2018).

Four papers described the benefits of older people and those PLiPWD residing within the general prison population (Dillon et al., 2019; Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018; Treacy et al., 2019; Williams et al., 2012). Those living with dementia reported a benefit from socialising with, and being cared for by, younger people (Dillon et al., 2019; Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018; Williams et al., 2012). The presence of older people also reportedly calmed younger prisoners (Dillon et al., 2019; Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018; Williams et al., 2012). Importantly, removing people from their prison social networks may have a detrimental effect (Williams et al., 2012), and living on specialist units can be stigmatising (Treacy et al., 2019).

Regime and activities

The maintenance of prisons regimes is the primary focus of prison officers (Brooke & Jackson, 2019). However, there was a reported need (n = 19) for PLiPWD to have equal access to activities and services including work, education, gym, library and day centres where they exist, as well as a structured and varied regime on the wing on which they were accommodated, and support to access these. This support could include providing adequate seating (Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011), or giving prisoners more time to accomplish activities, and to assist if needed (Brooke & Jackson, 2019; Goulding, 2013; Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018; Hodel & Sanchez, 2013). Other recommendations included an overall relaxation of regimes (Gaston & Axford, 2018; Treacy et al., 2019), an ‘open door’ policy (Brown, 2016; Cipriani et al., 2017; Goulding, 2013; Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Prisons, 2014; Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Prisons, 2017b; Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018; Treacy et al., 2019), more visible staff (The King's Fund, 2013), and creating a more communal social environment (Christodoulou, 2012). On-wing social activities are described in Table 11.

Having on-wing work available or alternative means for prisoners who are unable to work to make money was also reportedly important (Christodoulou, 2012; Department of Health, 2007; Gaston, 2018; Gaston and Axford, 2018; Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Prisons, 2014, 2016, 2017b; Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018; Moll, 2013; Murray, 2004; Treacy et al., 2019; Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011). It was suggested that people with dementia should have the chance to work if wanted, and adaptations could be made to work programmes or working days made shorter to facilitate this. Some prisons had specific roles which involved lighter, simple, repetitive tasks such as gardening (Baldwin & Leete, 2012; Brooke & Jackson, 2019; Inspector of Custodial Services, 2015; Moll, 2013; Treacy et al., 2019). Day centres existed in some prisons, or were thought to be feasible (Department of Health, 2007; Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018; Moll, 2013; Treacy et al., 2019; Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011), and it was suggested that attendance at these could constitute meaningful paid activity (Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018). The centres were largely developed and facilitated by charities, and ran a wide variety of social, therapeutic, recreational, arts and advice-centred activities (Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018; Moll, 2013).

Equal access to educational activities, including rehabilitation and offending behaviour programmes, was highlighted as important, particularly where attendance is needed to facilitate people’s progression through the system (Booth, 2016; Brooke & Jackson, 2019; Dillon et al., 2019; Department of Health, 2007; Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018). Some prisons provided, or felt there was a need for, particular educational activities for PLiPWD and adaptations may be, or have been, made to learning materials and equipment, content and pace (Brooke & Jackson, 2019; Department of Health, 2007; Gaston, 2018; Gaston & Axford, 2018; Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018; Treacy et al., 2019; Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011). Dedicated library sessions have been designated in some prisons, and some libraries can and do stock specialist resources including books, audiobooks, reminiscence packs and archives of local photos, music and DVDs (Department of Health, 2007; Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018;Treacy et al., 2019; Williams, 2014). Educational materials could and have been available between sessions to aid memory with distance learning also possible (Brooke & Jackson, 2019; Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018). Suggestions for alternatives for PLiPWD focused on activity and stimulation (du Toit & Ng, 2022; Gaston, 2018; Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018), preparing for retirement classes (Department of Health, 2007), health promotion (Brooke et al., 2018; Christodoulou, 2012; Gaston & Axford, 2018; Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018; Maschiet al., 2012; Murray, 2004; Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011), the arts (Brooke & Jackson, 2019) and IT classes (Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018). Prisoner forums or representative could also be consulted regarding regimes and activities (Moll, 2013; Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018; Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011). Challenges to regimen and activities are described in Table 12.

Environment

A large number (n = 42) of the included papers discussed changes that prisons had made, or should make, to the built environment in order to be more suitable for PLiPWD – in one study in England and Wales, around half of prisons surveyed had made such environmental modifications (Forsyth et al., 2020). These focused on: (i) prisoners’ cells, (ii) bathrooms, (iii) dining hall, (iv) outside space and recreation areas, and (v) overall general prison environment (Table 13).

Problematically, the age and dementia-inappropriateness of buildings are considered a challenge (Baldwin & Leete, 2012; Brown, 2016; Dementia Action Alliance, 2017; Forsyth et al., 2020; Goulding, 2013; Inspector of Custodial Services, 2015; Mistry & Muhammad, 2015; Prisons and Probation Ombudsman, 2016; Treacy et al., 2019). Difficulties in navigating prisons where everywhere looks the same (Dementia Action Alliance, 2017; Murray, 2004; Treacy et al., 2019), and the lack of budget (HMP Littlehey, 2016; HMP Littlehey, 2016; Inspector of Custodial Services, 2015; Treacy et al., 2019) were also reported issues. It was suggested that the use of dementia-friendly environmental checklists could be useful, potentially with input from occupational therapists, health and social care, and dementia charities and in-house education, work and estates departments (Brown, 2014; Christodoulou, 2012; Dillon et al., 2019; Goulding, 2013; HMP Littlehey, 2016; Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018; Hodel & Sanchez, 2013; Peacock et al., 2018; Sindano & Swapp, 2019; Treacy et al., 2019). Hope was expressed that newly built prisons would be more dementia-friendly (Dementia Action Alliance, 2017; Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018; Williams et al., 2012).

Family

Formal policies and procedures should be in place to help maintain links between family and prisoners, and to foster an understanding of the central importance of families particularly for PLiPWD (Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Prisons, 2016; Treacy et al., 2019). Some papers described how prisons could support contact by: giving help and additional time to make telephone calls and arranging visits in quieter spaces (Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018; Prisons and Probation Ombudsman, 2016; Treacy et al., 2019); increasing the number of visits (Jennings, 2009); and allowing for accumulated visits or transfers to other prisons for visits closer to home (Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018). Family communication – additional information can be found in Table 14.

External organisations

One review suggested that external voluntary agencies were not often contacted or referred to, despite their potential benefits in terms of costs and support for staff and PLiPWDs (du Toit et al., 2019). However, other papers reported that charities for PLiPWD, or older people, were involved in (or were recommended to be involved in): designing and/or delivering dementia training; being part of MDTs; informing the design of referral processes, screening, assessment and case finding tools; consulting on environmental design; creating and delivering social care plans (including running activity centres); advice and support; advocacy and; co-facilitating a cognitive stimulation therapy group (Alzheimer’s Society 2018; Brooke et al., 2018; Brown, 2014, 2016; Correctional Investigator Canada, 2019; Department of Health, 2007; du Toit & Ng, 2022; du Toit et al., 2019; Gaston, 2018; Gaston & Axford, 2018; Goulding, 2013; Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Prisons, 2014; HMP Hull, 2015; Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018; Hodel & Sanchez, 2013; Moll, 2013; Peacock et al., 2018; Prisons and Probation Ombudsman, 2016; Sindano & Swapp, 2019; Tilsed, 2019; Treacy et al., 2019; Williams, 2014). It was also recommended that external organisations need to have a better knowledge and understanding of prisons and people living in prison, in order to better manage risk, and for clear information sharing protocols (du Toit & Ng, 2022).

(iv) Transfers

During the course of their sentence, people in prison may be transferred to other prisons for various reasons or to receive treatment in hospital. The need for MDT transfer plans to be developed was reported (Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011), as was the need to limit the number of prisoner transfers as moving accommodation is likely to have an adverse effect (Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018; Patterson et al., 2016). It was recommended that transfers should take the distance from family and friends into account (Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018), and that the ‘receiving’ facility (prison or healthcare setting) should be liaised with regarding health and social care, and risk (Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018; Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011) to ensure continuity of care (Cipriani et al., 2017). A standard document transfer protocol was also postulated as useful, as documents need to be forwarded quickly as well (Brown, 2016; Tilsed, 2019; Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011). At the receiving facility, it was suggested that assessments and care plans should be reviewed on the day of the transfer (Brown, 2016; Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2017; Welsh Government, 2014), and for re-inductions to be facilitated for prison transfers (Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018).

(v) Release and resettlement

Most prisoners will be released from prison at the end of their sentence, although a number may die before their time is served. A number of areas were highlighted regarding the release and resettlement of PLiPWD, including the possibility of early release due to dementia.

Early release

A number of papers advocated for compassionate release policies and their actual use, or alternative custodial placements such as halfway houses or secure nursing homes, that would effectively result in the early release of PLiPWD (Brown, 2016; Cipriani et al., 2017; Correctional Investigator Canada, 2019; Dementia Action Alliance, 2017; Department of Health, 2007; du Toit & Ng, 2022; du Toit et al., 2019; Fazel et al., 2002; Gaston & Axford, 2018; Goulding, 2013; Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018; Hodel & Sanchez, 2013; Inspector of Custodial Services, 2015; Maschi et al., 2012; Mistry & Muhammad, 2015; Pandey et al., 2021; Turner, 2018; Williams et al., 2012). Although, it has also been noted that early release may not be a popular idea for some sections of the community (du Toit et al., 2019; Garavito, 2020), it was also suggested that raising community awareness of dementia may ameliorate this (du Toit & Ng, 2022). It was reported that prisoners with dementia should be considered in any criteria set forth for early release, particularly given the high cost/low risk ratio which they represent (Baldwin & Leete, 2012; Correctional Investigator Canada, 2019; Department of Health, 2007; Goulding, 2013; Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018; Inspector of Custodial Services, 2015; Maschi et al., 2012; Murray, 2004; Williams et al., 2012). For prisoners who do not understand the aims of prison, continuing to hold them may be a contravention of human rights and equality laws – particularly where health and social care is inadequate (Baldwin & Leete, 2012; Dementia Action Alliance, 2017; Fazel et al., 2002; Gaston & Axford, 2018; Murray, 2004). It was also emphasised that the existence of units and programmes for PLiPWD should not be used to legitimise prison as an appropriate place for PLiPWD (Correctional Investigator Canada, 2019). More information can be found in Table 15.

Resettlement

Ten different areas were identified in the literature which related to the issues PLiPWD leaving prison may face on their release and resettlement into the community, these were:

-

(a) In-prison release preparation

Specific pre-release programmes or services for older people or those living with dementia may be required (Department of Health, 2007; Williams et al., 2012), with prisoners being cognitively screened prior to release (Goulding, 2013), although the latter was only found in 10% of prisons in one study (Forsyth et al., 2020). Other suggestions for programme content included: self-efficacy, health, staving off dementia and associated anxiety, accessing services, addressing institutionalisation, setting up email addresses, and the provision of information packs on national, regional and local services and resources (Department of Health, 2007; Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018; Williams et al., 2012).

It has been suggested that release plans and transitions be facilitated by an MDT including prisoners, the voluntary sector, offender managers, and other appropriate community-based organisations (du Toit et al., 2019; Feczko, 2014; Goulding, 2013; Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018; Inspector of Custodial Services, 2015; Moll, 2013; Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011). Recommended plan content included: risk management strategies, health, social care, housing, finance, employment, leisure and voluntary sector considerations (Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011). It was also suggested that Circles of Support and Accountability (CoSA), primarily associated with sex offenders, could be set up for PLiPWD as a means to support those leaving prison and settling back into the community particularly without family support (Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018).

Challenges to release preparation were identified as: a lack of resources, (Turner, 2018) the lack of clarity regarding staff resettlement roles (Inspector of Custodial Services, 2015), and the lack of resettlement provision offered at sex offender prisons in England and Wales (Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018).

-

(b) Family

A number of papers reported the key role that family and friends can or do play in supporting PLiPWD leaving prison, and that this should be supported or facilitated by prison staff (Brown, 2016; Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018; Goulding, 2013). Initially this could include encouraging diagnosis disclosure (Dillon et al., 2019), using prison leave to maintain relationships (Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018), involvement in discharge planning (Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011), and placing prison leavers close to family upon release and ensuring family are supported (Correctional Investigator Canada, 2019; Gaston & Axford, 2018). Where PLiPWD lack family, setting up CoSAs as described above may be useful (Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018).

-

(c) Probation

It was suggested that probation staff should have training to work with older people, and that some offender managers could specialise in this work (Department of Health, 2007; Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011). Probation officers or offender managers are or can be involved in resettlement planning, (Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018; Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011), arranging accommodation (Inspector of Custodial Services, 2015), liaising with agencies such as health care or social services, checking that PLiPWD are accessing these services and disseminating reports of to-be released prisoners to relevant parties (Department of Health, 2007; Moll, 2013; Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011). Importantly, the forwarding of important documents to offender managers by the prison should be routine (Department of Health, 2007; Moll, 2013). It was also recommended that probation staff should visit people in prison before release if they live out of area (Department of Health, 2007). The work of probation services was reportedly hampered by limited resources (Brown, 2016).

-

(d) Health

Continuity of care upon release can be difficult, and it was suggested that it could be a role of prison healthcare to ensure this (including registering with the local GP and dentist (Cipriani et al., 2017; Department of Health, 2007; Gaston, 2018; Gaston & Axford, 2018; Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018; Inspector of Custodial Services, 2015; Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011). There appeared to be some differences regarding the distribution of full healthcare reports to offender managers and other appropriate agencies with some prisons sending them, some only if requested, and some not providing them on grounds of confidentiality (Moll, 2013). Typically, it was recommended that it was better for to-be released older prisoners if these reports were disseminated (Department of Health, 2007). It was also suggested that healthcare staff in prison and from the community form part of multi-disciplinary release planning, and that these plans include health considerations and healthcare staff advice on issues of accommodation (du Toit & Ng, 2022; Inspector of Custodial Services, 2015; Moll, 2013; Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011).

-

(e) Social care

Some papers reported that social workers can and should be involved in the process of resettlement (Department of Health, 2007; Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011) and release preparation (Goulding, 2013). Continuity of social care arranged with the local authority was also recommended (Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018; Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011).

-

(f) Accommodation

Release planning should include plans for accommodation, and involve housing agencies or care services in the community in that planning (Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011). Importantly, people in prison may need help in registering for housing, and their homes may be in need of adaptation in response to their health or social care needs (Department of Health, 2007; Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018). Nursing homes and other care providing facilities were reported to be reluctant to accommodate people who have been in prison (Brown, 2014; Brown, 2016; Booth, 2016; Correctional Investigator Canada, 2019; du Toit et al., 2019; Gaston, 2018; Garavito, 2020; Goulding, 2013; Inspector of Custodial Services, 2015). This was described as particularly the case for those who were living with dementia (Brown, 2014; Correctional Investigator Canada, 2019; Dillon et al., 2019), with further issues reported in accommodating those who have committed sex offences (Brown, 2014, 2016; Dillon et al., 2019; Garavito, 2020; Inspector of Custodial Services, 2015). Concerns regarding the safety of other residents and the views of their families, and the rights of victims in general, were cited as reasons behind these placement difficulties (Brown, 2014; Goulding, 2013) – one paper reported that there had been community protests (Brown, 2016).

It was suggested that prisons need to build better relationships with care providers in the community, which had reportedly been forged by some (Brown, 2016; Goulding, 2013; Inspector of Custodial Services, 2015), and that they could also provide education and support to these services (Booth, 2016). However, it was also noted that there may be a need for specialist residential units to be created in the community for people released from prison with dementia (Inspector of Custodial Services, 2015), with an example of a state-run facility for ex-prisoners in the United States (Goulding, 2013), and particular attention for younger ex-prisoners with dementia (Brown, 2014). A number of papers reported that if accommodation could not be arranged for people, this largely resulted in them remaining in prison until it was (Correctional Investigator Canada, 2019; Goulding, 2013; Inspector of Custodial Services, 2015; Peacock et al., 2018; Soones et al., 2014).

-

(g) Finance

Imprisonment likely leads to a loss of income, meaning that older prisoners who may have served more lengthy sentences are likely to be poorer, particularly if unable to work in prison (Baldwin & Leete, 2012; Gaston, 2018). Therefore, it was suggested that release planning ought to include issues of finance (Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011). Given that it has been suggested that people in prison should be given advice on pensions and welfare benefits, and help to arrange these (Department of Health, 2007; Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018; Goulding, 2013), addressing this would seem to be an area of particular use for older people leaving prison who may have additional problems in these areas, and for those who may need assistance in arranging their financial affairs because of their deteriorating health problems.

-

(h) Employment and education

People’s employment prospects are likely to be impacted upon release from prison, particularly for older people who may have served long sentences (Gaston, 2018). Where appropriate, it was recommended that release planning should include issues around employment (Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011), that information packs for people should include sections on education and employment, and that it could be useful to help people make links with the Department for Work and Pensions (Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018).

-

(i) Leisure

Leisure activities and resources could be considered in release planning, and included in pre-release information packs for prisoners (Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018; Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011).

-

(j) Charities and voluntary sector organisations

It was recommended in a number of papers that charity and voluntary sector organisations working with PLiPWD be involved in release planning (Department of Health, 2007; du Toit et al., 2019; Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018; Moll, 2013; Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011), continuity of care (Moll, 2013), and in providing support during the transition and after (du Toit & Ng, 2022; Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011). It was also suggested that in general it would be useful for PLiPWD to have contact with these organisations (Department of Health, 2007; Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018; Inspector of Custodial Services, 2015), and that they may be well-placed to develop information packs for prisoners on release regarding local amenities, services and resources (Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018).

(vi) Cross-cutting themes

Eight more generalised concerns were also described which had a clear impact on the passage of PLiPWD through prison, on release and resettlement in the community, and on the issues raised thus far in the review.

Principles-philosophy

The principles suggested to underpin the support of PLiPWD are that it should be person-centred, holistic, adhere to human rights and dignity principles, proactive, health promoting, and enabling – making choices but supported if needed (Brown, 2014, 2016; Christodoulou, 2012; Cipriani et al., 2017; Correctional Investigator Canada, 2019; Department of Health, 2007; Dillon et al., 2019; du Toit & Ng, 2022; Gaston & Axford, 2018; Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Prisons, 2017b; Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018; Mackay, 2015; Maschi et al., 2012; Treacy et al., 2019; Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011; Wilson & Barboza, 2010). Conversely, clashes in philosophies between prison staff, and health and social care staff have been reported with security trumping care in many cases, which can have a negative impact (du Toit & Ng, 2022; Gaston, 2018; Gaston & Axford, 2018; Goulding, 2013; Mackay, 2015; Murray, 2004; Patterson et al., 2016; Prisons and Probation Ombudsman, 2016; Treacy et al., 2019; Williams, 2014). It was suggested that positioning dementia as more than just a health issue and fostering a whole-prison care-custody model or approach, with clearly defined roles for ‘care’ and ‘custody’, may be useful in resolving this (du Toit & Ng, 2022; Public Health England, 2017b; Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011).

Resources

A number of papers (n = 15) reported that budget and resource limitations had a variety of negative impacts including difficulties in providing: appropriate assessment, support and accommodation to PLiPWD; specialist accommodations, plans for which were then curtailed; delivering programmes and activities; healthcare cover; and, staff training (Booth, 2016; Christodoulou, 2012; Correctional Investigator Canada, 2019; Dementia Action Alliance, 2017; Dillon et al., 2019; du Toit et al., 2019; du Toit & Ng, 2022; Goulding, 2013; HMP Hull, 2015; Jennings, 2009; Mackay, 2015; Moll, 2013; Moore & Burtonwood, 2019; Pandey et al., 2021; Patterson et al., 2016; Peacock et al., 2018; Treacy et al., 2019; Turner, 2018). Ultimately, lack of resources has reportedly led to a system that is not able to cope appropriately with PLiPWD (Moll, 2013; Williams et al., 2012; Wilson & Barboza, 2010), with associated problems transferring out of the prison system into probation and care systems when people are released (Williams et al., 2012).

Capacity

It has been suggested that PLiPWD in prison should be treated as if they have capacity to make decisions such as giving or withholding consent for treatment, unless it is proven otherwise. This is consistent with legislation such as the Mental Capacity Act (Prisons and Probation Ombudsman, 2016). It has been recommended that healthcare staff should conduct capacity assessments if there are concerns (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2017; Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011), and be trained to do so (Maschi et al., 2012; Welsh Government, 2014). It is of note that an ombudsman report showed that PLiPWD who died lacked access to mental capacity assessments (Peacock et al., 2018). For PLiPWD, who are likely to lack capacity as their condition progresses, early education about, and development of, advance directives has been advocated (Brown, 2016; Cipriani et al., 2017; Inspector of Custodial Services, 2015; Maschi et al., 2012; Prisons and Probation Ombudsman, 2016), and staff should be trained on this (Maschi et al., 2012). It has also been suggested that family members, independent mental capacity advocates or healthcare proxies could or should be used for PLiPWD who lack capacity in making care, welfare and financial decisions (Brown, 2016; Soones et al., 2014), supported by legislation and oversight, as opposed to prison or healthcare staff making decisions (Correctional Investigator Canada, 2019).

‘Risk’

The issue of ‘risk’ related to PLiPWD revolves around four areas: (i) assessment, (ii) management, (iii) disciplinary procedures, and (iv) safeguarding. Full details can be found in Table 16.

There were a number of additional facets to risk concerns regarding PLiPWD described in the papers. There were concerns that the lack of understanding of the impact of dementia on people’s behaviour could ultimately lead to people being held in prison for longer periods on account of seemingly transgressive or aggressive behaviour that could in fact be related to their dementia difficulties (Dementia Action Alliance, 2017; Mistry & Muhammad, 2015; Treacy et al., 2019). In one study, a prisoner with dementia was transferred to another prison because staff felt that they were ‘grooming’ an officer (Treacy et al., 2019), likely lengthening their overall prison stay. There was also a recurring issue in fatal incidents investigations in England and Wales of prisoners being restrained whilst dying in hospital, a practice described as unnecessary in light of their likely frail state (Peacock et al., 2018; Prisons and Probation Ombudsman, 2016). One paper suggested linking future accommodation options and considerations for Release on Temporary Licence to a PLiPWD’s risk of reoffending, as well as the severity of their symptoms (Forsyth et al., 2020). Moore and Burtonwood (2019) also observed that a lack of risk assessment protocols was a barrier to release of PLiPWD., and as Table 16 suggests, a comprehensive risk assessment, applied by appropriately trained staff should make health and its impact on future offending more salient to aid this.

Choice

There were recommendations that PLiPWD should have the opportunity to make choices in their treatment and care. This included input into care plans or making informed decisions about their care (Department of Health, 2007; du Toit & Ng, 2022; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2017; Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011), as well as developing advance directives particularly early in a person’s sentence (Brown, 2016; Cipriani et al., 2017; Inspector of Custodial Services, 2015; Maschi et al., 2012; Pandey et al., 2021; Peacock et al., 2019; Prisons and Probation Ombudsman, 2016), and choosing ‘preferred’ places to die (Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018).

Protected characteristics

There was a reported need for culturally appropriate assessments, treatment and activities (Brooke et al., 2018; Department of Health, 2007; Hamada, 2015; Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011), spiritual support (Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011), multilingual information (Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011), and the recognition of gender differences in dementia healthcare needs (Brown, 2014; Department of Health, 2007; Williams et al., 2012). It was also highlighted that racism makes the experience of living with dementia in prison more problematic (Brooke et al., 2018; Brown, 2014; Correctional Investigator Canada, 2019). There were some examples of policy and practice within prisons which considered some protected characteristics: assessment tools in different languages (Patterson et al., 2016), additional support for PLiPWD to plan care (Department of Health, 2007; Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011), and the development of culturally appropriate care planning (Hamada, 2015). Hamada (2015) also advocated assessment and treatment that was culturally ‘competent’ and respectful, and which acknowledged the importance of culture and diversity.

An overall need to tackle dementia- and age-related stigma was also reported in some papers, and the need to foster cultures that are age-respectful should be reflected in staff training (Department of Health, 2007; Treacy et al., 2019; Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011), In addition, practices which openly discriminate such as the lack of: dedicated dementia resources (Turner, 2018), appropriate lower category prison places (Department of Health, 2007; Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011), and appropriate accommodation on release, which at times prevents release, should also be challenged (Correctional Investigator Canada, 2019; Forsyth et al., 2020; Ministry of Justice, 2013; Prisons and Probation Ombudsman, 2016). There was also a lack of research into the interaction between protected characteristics and dementia in prison (Brooke & Jackson, 2019; Treacy et al., 2019; Williams et al., 2012).

Collaboration

Many papers advocated the need for prisons and specialist dementia units to adopt a collaborative MDT approach drawing from staff teams across the prison regarding: the identification and support of prisoners with dementia, care planning, the disciplinary process, the development, dissemination and implementation of policy, and in environmental change and the building of new prisons (Brooke et al., 2018; Brown, 2014, 2016; Christodoulou, 2012; Cipriani et al., 2017; Dillon et al., 2019; Department of Health, 2007; Feczko, 2014; Forsyth et al., 2020; Gaston & Axford, 2018; Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Prisons, 2014, 2016; HMP Hull, 2015; HMP Littlehey, 2016; Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018; Inspector of Custodial Services, 2015; Moll, 2013; Patterson et al., 2016; Peacock et al., 2018; Peacock, 2019; Prisons and Probation Ombudsman, 2016; Sindano & Swapp, 2019; The King’s Fund 2013; Tilsed, 2019; Treacy et al., 2019; Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011, 2014; Williams, 2014). There were examples of prisoners collaborating with staff in the care of PLiPWD as peer supporters, and having joint staff-prisoner supervision and training (Brooke & Jackson, 2019), of joint staff-prisoner wing meetings in one prison (Treacy et al., 2019), and of the co-designing of services and activities in others (Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018; Treacy et al., 2019). It was suggested that this collaborative way of working should be supported by an information sharing protocol, clear definitions of staff and peer supporter roles and responsibilities, and training (Brooke & Jackson, 2019; Dillon et al., 2019; du Toit & Ng, 2022; HMP Littlehey, 2016; Turner, 2018). It was reported that there had been a lack of communication and coordination of this process in some prisons which had a negative impact on all involved (Brooke & Rybacka, 2020; Forsyth et al., 2020; Moll, 2013; Prisons and Probation Ombudsman, 2016).

It was also suggested that the prisons collaborate with healthcare, hospice and dementia specialists in the community and with external charitable organisations (Brooke et al., 2018; Brown, 2014; Cipriani et al., 2017; du Toit & Ng, 2022; Gaston, 2018; Gaston & Axford, 2018; Goulding, 2013; HMP Hull, 2015; HMP Littlehey, 2016; Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service, 2018; Moll, 2013; Peacock, 2019; Prisons and Probation Ombudsman, 2016; Sindano & Swapp, 2019; Tilsed, 2019; Treacy et al., 2019; Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011; Williams, 2014). In addition, inter-prison networks were recommended to be developed to share good practice across prisons (Dementia Action Alliance, 2017; Moll, 2013; Peacock et al., 2019; Prisons and Probation Ombudsman, 2016).

Information-sharing

A number of papers (n = 7) recommended the need for a clear information sharing protocol regarding the assessment and support of PLiPWD (Brooke et al., 2018; Dillon et al., 2019; Department of Health, 2007; Goulding, 2013; Moll, 2013; Tilsed, 2019; Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011), or a register (Forsyth et al., 2020). Particular attention to the interface between healthcare and prison staff and peer supporters was suggested, where it has been reported that privacy regulations have sometimes prevented contributions to collateral histories (Feczko, 2014) and the sharing of care plans, impairing their ability to offer appropriate support (Inspector of Custodial Services, 2015). Also, it may be against the wishes of the person with dementia, and informed consent should be sought (Forsyth et al., 2020; Moll, 2013). This lack of information can have a detrimental effect on a person’s health and wellbeing (Brown, 2014, 2016; Feczko, 2014; Inspector of Custodial Services, 2015), and so discussion of this was highlighted as important, particularly where the safety of the person or others were concerned (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2017). A care plan which gives only very basic information to staff and peer supporters was used in a couple of prisons (Goulding, 2013; Williams, 2014).

There also appeared to be variance with respect to whether healthcare staff disclose a dementia diagnosis to the person diagnosed with dementia. A couple of prisons’ policy was to share a diagnosis and involve family in doing so (Maschi et al., 2012; Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011; Wilson & Barboza, 2010), however, in one prison disclosed if a person was judged to be able to cope with it, and another only disclosed if asked (Brown, 2016). The importance of disclosure to family allowing them to contribute to assessments, planning and support was also emphasised in some papers (Brown, 2016; Dillon et al., 2019; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2017; Welsh Government and Ministry of Justice, 2011).

Discussion

This review has explored the literature regarding all parts of the custodial process and its impact on people living in prison with cognitive impairment and dementia, which includes: reception, assessment, allocation, training, policy, healthcare, accommodation, adaptation, routine, access to family and external agencies, transfer and resettlement. We found evidence that problems had been identified in each of these parts of the process. We also identified a number of cross-cutting themes which interacted with the issues identified across the prison journey including: principles or philosophy regarding care; capacity; resources; considerations of risk; scope for choice; peoples’ protected characteristics; collaboration; and, information sharing. Broadly, our findings were similar to those found in previous reviews, regarding the problems with the prison process identified, and the lack of robust outcomes, and policy guidance regarding PLiPWD (Brooke and Rybacka, 2020; Peacock et al., 2019).

The aim of this review was to identify areas of good practice and for recommendations that could inform the development of prison dementia care pathways. There is a considerable breadth to the findings, but the main recommendations that have arisen from the review are:

-

To screen prisoners for cognitive difficulties at reception, from either 50 or 55 years

-